What you need to know

Adapted from Canadian Cancer Society.1

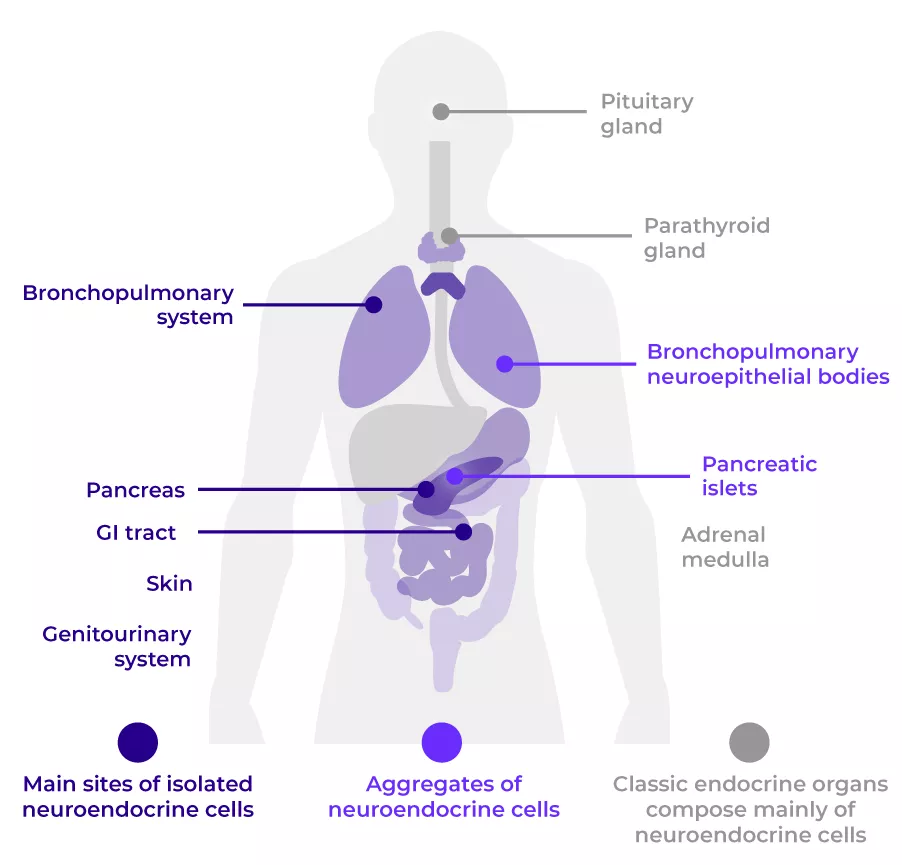

Definition and distribution of NETs

NETs are a group of neoplasms that originate in secretory cells known as neuroendocrine cells, which are distributed throughout the body.1,2

They are located in three broad areas:

Isolated neuroendocrine cells, scattered throughout most tissues1,3

Aggregates of neuroendocrine cells in organs3

Classic endocrine glands1

Adapted from Oronsky B, et al. 2017.5

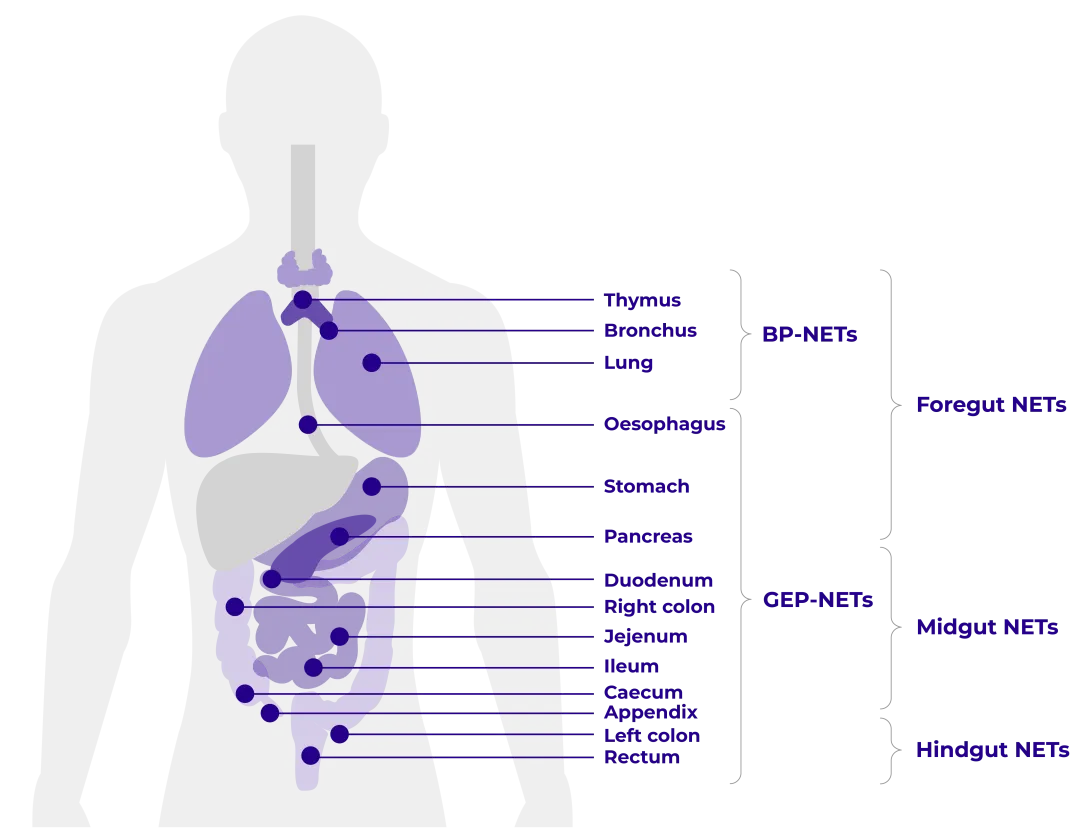

Anatomical classification of NETs

NETs are classified according to their anatomical site of origin, with the vast majority arising in the gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) or bronchopulmonary (BP) tracts (GEP-NETs and BP-NETs, respectively).4

NETs are traditionally subclassified according to the embryological origin of their site:5

Foregut

Midgut

Hindgut

The nature of NETs

Not only do NETs differ in their anatomical site, they also vary in their level of differentiation and ‘aggressiveness’ (grading).4,6

Differentiation

Refers to the extent to which tumour cells morphologically resemble healthy cells from the same tissue4,6

By definition, NETs are well-differentiated7

NETs are usually organised into well-developed architectural patterns5,8

The invasive and metastatic potential of NETs is variable7

Grading

NETs are given a histological grade which refers to the aggressiveness of the tumour, i.e., G1, G2 or G34

Higher-grade tumours are associated with negative patient outcomes8,9

Well-differentiated NETs are nearly always G1 or G2 (though some can be G3); poorly differentiated tumours are referred to as neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) and are always G34,7

Functioning and non-functioning NETs2,4,10

In the case of NETs, increased proliferation of neuroendocrine cells sometimes leads to hypersecretion of hormones.4 When NETs cause clinical symptoms due to hormone hypersecretion, they are described as ‘functioning’. However, most NETs do not produce biologically active hormones and are termed ‘non-functioning’.4

Type of functioning NET | Hormone(s) secreted | Anatomical site |

Functioning carcinoid | Serotonin, tachykinin, prostaglandins, 5-hydroxytryptophan, histamine | Small intestine, lung or pancreas |

ACTHoma | Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) | Pancreas, bronchus, thymus |

Insulinoma | Insulin | Pancreas |

Gastrinoma | Gastrin | Gastrinoma triangle |

Glucagonoma | Glucagon | Pancreas |

PPoma | Pancreatic polypeptide (PP) | Pancreas |

Somatostatinoma | Somatostatin | Pancreas/duodenum |

VIPoma | Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) | GEP tract, adrenal gland |

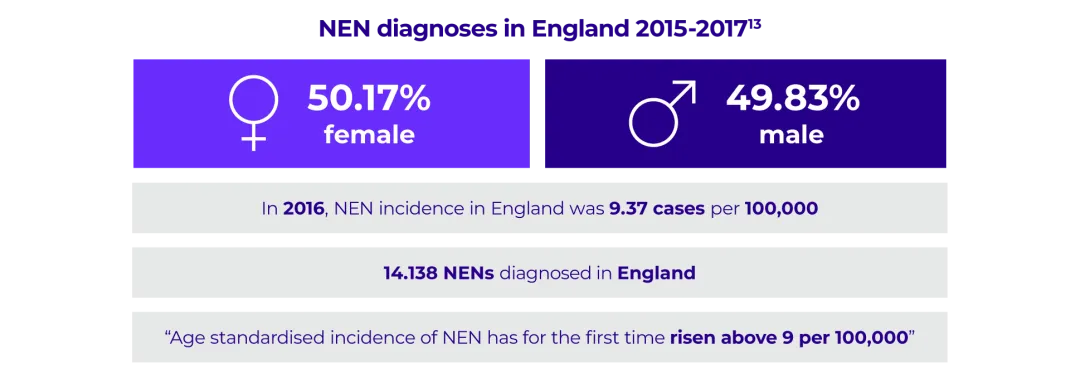

Incidence of NETs

Historically considered as rare tumours, NETs are becoming increasingly common.11 NET incidence has increased >500% in the last three decades. Approximately 6 in every 100,000 people will develop a NET.11

In the UK:

The age-adjusted incidence of GEP-NETs increased 3.8- to 4.8-fold from 1973 to 200712

In England specifically, neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN) incidence rose to 9.37 per 100,000 in 2016, remaining at a similar rate in 201713

Adapted from White BE, et al. 2019.13

Symptoms of NETs

The majority of NETs are non-functioning and symptoms, if they do occur, tend to be vague and non-specific.4,5

Symptoms associated with BP-NETs

BP-NETs are associated with wheezing, coughing, haemoptysis, dyspnoea, chest pain and recurrent pneumonia4,5,14

Peripherally located lung NETs are usually asymptomatic5

Symptoms associated with GEP-NETs

The most prominent symptoms are abdominal pain and change in bowel habit (due to mass effects of the tumour causing intermittent bowel obstruction)4,14

Fatigue is particularly prevalent in those with pancreatic NETs14

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; BP, bronchopulmonary; GEP, gastroenteropancreatic; GI, gastrointestinal; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; NEN, neuroendocrine neoplasm; NET, neuroendocrine tumour; PP, pancreatic polypeptide; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide.

References

Canadian Cancer Society. The neuroendocrine system. Available at: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/neuroendocrine/what-is-neuroendocrine-cancer/the-neuroendocrine-system [Accessed October 2025].

Kidd M, et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;1:131–153.

Ameri P & Ferone D. Neuroendocrinology 2012;95:267–276.

Raphael M, et al. CMAJ 2017;189:E398–E404.

Oronsky B, et al. Neoplasia 2017;19:991–1002.

Chung C. Am J Health Syst Phar 2016;73:1729–1744.

Rindi G, et al. Mod Pathol 2018;31:1770–1786.

Cavalcanti M, et al. Int J Endocr Oncol 2016;3:203–219.

Dasari A, et al. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1335–1342.

Asha H, et al. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2011;15:346–348.

Frilling A, et al. Endocr Relat Cancer 2012;19:R163–R185.

Fraenkel M, et al. Endocr Relat Cancer 2014;21:R153–R163.

White BE, et al. Endocr Abstr 2019; 68:OC3.

Basuroy R, et al. Neuroendocrinology 2018;107:42–49.

UK | October 2025 | FA-11462546

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard.